Access of the most disadvantaged to higher education is a challenge to face in Latin America and the Caribbean

The conference organized by the UNESCO International Institute for Higher Education in Latin America and the Caribbean (IESALC) highlights the advances, but also points out the challenges, faced by the region; the institution’s director emphasizes the aggravation of the situation due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

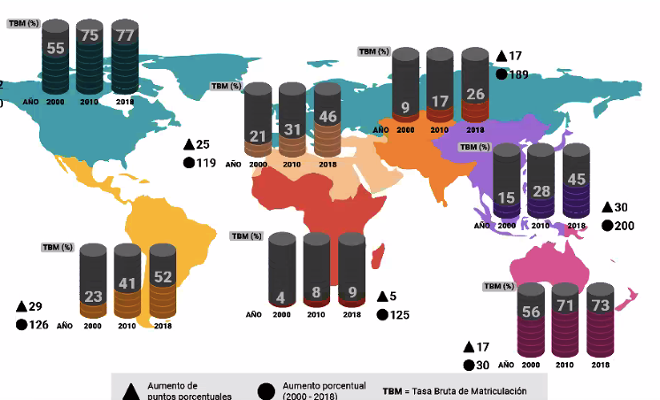

Between 2000 and 2018, access to higher education increased worldwide. The gross enrollment rate (percentage of the population enrolled in relation to the total population of the recommended age group) increased from 19% to 38%.

In the Latin America and Caribbean region, which had the second best performance in the world, the gross enrollment rate in higher education increased from 23% to 52%.

Source: IESALC

Another celebrated result was the increased access of women to higher education. After 19 years, the increase in female enrollment in university institutions in Latin America and the Caribbean points to the existence of policies adopted to ensure gender equality in the region.

There are, however, winds of change blowing in some directions; in others, transformations have remained dormant. When we look at the relationship between access to higher education and the social and economic profile of students, we realize that enrollment is still concentrated in the wealthier social strata of society. Between 2000 and 2018, the percentage of growth in the gross enrollment rate among the poorest in the region was 5%, reaching 10% in 2018; and among the wealthiest, the growth rate was 22%, reaching 77% in 2018, with exclusion scenarios accentuated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Source: IESALC

This and other challenges were discussed during the Conference “Inequalities in Access to Higher Education and Disadvantaged Populations in the Latin American and Caribbean Region in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic,” held virtually by the UNESCO International Institute for Higher Education in Latin America and the Caribbean (IESALC).

The event, which took place last Tuesday, November 17, 2020, with 77 participants, including university authorities, academics, teachers and specialists, was held as part of the third edition of World Access to Higher Education Day (WAHED, 2020), a series of conferences organized by the National Educational Opportunities Network (NEON) that began in Australia, Asia, Africa, Europe, North America and now reaches Latin America and the Caribbean.

Social commitment

“How can we guarantee that the least prosperous populations have the same opportunities to access higher education? What initiatives are being taken by institutions to promote access to higher education, particularly for the most vulnerable groups? What public policies have been adopted in Latin America and the Caribbean? And looking ahead, what could be done to further democratize access to higher education in the region? ”

These were the questions that the director of IESALC, Francesc Pedró, asked the participants during the opening of the Conference. After presenting data that points to a better performance of the region in recent years, the director referred the questions to the four guests, noting that the challenges are still part of the region’s reality. The guests at the Conference were: Sandra Goulart Almeida, rector of the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), in Brazil; and vice president of the Montevideo Group University Association; Sir Hilary Beckles, Vice Chancellor of The University of the West Indies and President of Universities Caribbean; Marcelo Knobel, rector of the State University of Campinas (Unicamp), also in Brazil; and Rodrigo Arim, rector of the University of the Republic (UDELAR), in Uruguay.

Director of IESALC, Francesc Pedró. Photo: Marcílio Lana.

Pedró maintains that the main objective is to continue on the path of democratizing access to higher education, and warns that the COVID-19 pandemic has aggravated the existing adverse conditions. “Our current context is adverse. The political and economic scenario is not favorable, but I invite the institutions of our region to stand firm. Our commitment is to democratize access,” he said.

The director of IESALC called on the rectors, university leaders and professors to “go out into the streets in search of students.” “Those who are not enrolled, but who should be, must be found. In the great classical universities it is frequently remembered that the University is the Alma Mater, that is, the Mother of Souls. We must find the most vulnerable students and make sure they have the necessary conditions to access higher education”.

Access and permanence

Sandra Goulart Almeida, vice-president of the Asociación Grupo de Universidades Montevideo (Montevideo University Group Association) and rector of the UFMG, pointed out that the higher education system in Brazil is different: 11.6% of the enrollment is concentrated in public higher education institutions and another 88.4% in private ones. The rector pointed out that measures to try to ensure that a greater number of young people enter higher education, were taken in Brazil. She recalled that between 2005 and 2018, the number of students in Brazilian higher education rose from around 550,000 to over 1.3 million, but stressed that “the challenges are still great”.

In Brazil, the National Education Plan establishes the goal for 33% of young people, between 18 and 24 years old, to enter higher education by 2030. In 2018, that percentage was 23%.

“There was a great expansion in our federal educational system for that period,” said the rector, recalling the adoption, in 2007, of the Federal University Restructuring and Expansion Plan (Reuni), a project that expanded the offer of student seats and courses, and ensured the internalization of university campuses. The rector also referred to the 2012 “Quota Law”, and the 2016 “Law of PWD”, for people with disabilities.

Sandra Goulart Almeida, vice-president of the Asociación Grupo de Universidades Montevideo and rector of the UFMG. Photo: Marcílio Lana.

“Despite this, we are still far from eliminating the inequalities in access to higher education,” reflected the rector of UFMG. The Brazilian specialist highlighted some measures adopted at UFMG, presenting projections of the University for the future post-pandemic period. “Today we are very concerned not only about access, but also about student permanence in the University,” she explained. “Today we face a very sad situation, aggravated by the pandemic, but above all by the federal government’s current policy, which has reduced investment in public universities,” she warned.

Social Mobility

Sir Hilary Beckles, vice-rector of The University of the West Indies and president of Universities Caribbean. Photo: Marcílio Lana.

“In terms of the gender issue, at the moment in The University of the West Indies, which is the largest university in the Caribbean, we have 75% female enrollment of a total of 55.000 students. This is a reversal in terms of gender balance from how it was 30 years ago, it was 75% male, now is 75% female”, he celebrates. For Beckles, who is also president of Universities Caribbean, access to higher education is linked to the process of nation building, sovereignty and economic and social development.

The vice-chancellor of The University of the West Indies points out that one of the region’s great problems is the emigration of university graduates: “We are also suffering a tremendous brain drain from the islands of the Caribbean. Some forty percent of our university graduates emigrate to Canada, the US, and Europe, so we are investing heavily and our young people emigrate five years after their graduation”. According to Sir Hilary Beckles, “this has to do with the inability of the public and private sectors to absorb them. The economic system is not diversified and dynamic enough and the private sector can not attract, sustain and retain university graduates.

Admission processes are not inclusive

Rector of the Universidade Estadual de Campinas (Unicamp), Marcelo Knobel. Photo: Marcílio Lana.

The rector of the Universidade Estadual de Campinas (Unicamp), Marcelo Knobel, draws attention to the issue of admission processes. According to him, about 90 thousand young people should enroll, next year, in the admission process (called vestibular in Brazil) at Unicamp. But only 3,300 will be able to enter the institution. “The process is very difficult and ends up creating what we call the phenomenon of self-exclusion. Many young people, discouraged by an absurd competition, end up giving up”, emphasizes Knobel.

The leader of the Brazilian state university maintains that it is necessary to seek fairer and more inclusive processes. “We need to deconstruct the idea of the admission process as the only way to enter. At Unicamp we have adopted certain measures such as ProFis, an interdisciplinary training program that ensures that the best students of public high schools in Campinas [city where Unicamp is located], have direct access to higher education without having to go through an admission process,” he clarifies.

“Our program is 10 years old and we serve 120 students a year. We have achieved good results: 80% of the benefited students have a family income per capita of minimum wage; 40% are black (black and brown); and 90% are the first generation, in their families, to have enrolled in higher education,” he adds.

Decentralization

Rodrigo Arim, Rector of the University of the Republic of Uruguay. Photo: Marcílio Lana.

Rodrigo Arim, Rector of the University of the Republic of Uruguay, maintains that decentralization should be conceived as a strategy for the inclusion of students in higher education. The Uruguayan university leader reports that 80% of higher education enrollments are concentrated in the University of the Republic. There, explains Arim, there is no access mechanism like the Brazilian admission processes. “We are a country and a university with a democratic vocation, which is why we think it is fundamental to decentralize opportunities, to get out of the big cities and offer opportunities in the interior of the country,” he emphasizes.

Arim highlights that there is still a great challenge facing his country. “In 1988, we had 61 thousand students. Last year we reached the level of 140 thousand enrollments in higher education. In the next four years, the expectation is that 20 thousand new students per year will enter Uruguayan higher education. We need to find conditions for student financing to guarantee their permanence,” he adds.

RELATED ITEMS